Israel's leaders have declared that Hamas will be wiped off the face of the Earth and Gaza will never go back to what it was.

"Every Hamas member is a dead man," Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said after fighters from the militant group killed 1,300 people in a brutal attack on Israel.

The goal of Operation Swords of Iron appears far more ambitious than anything the military has planned in Gaza before. But is that a realistic military mission, and how can its commanders possibly fulfil it?

A ground invasion of the Gaza Strip involves house-to-house urban fighting and carries immense risks to the civilian population. Air strikes have already claimed hundreds of lives, and more than 400,000 people have fled their homes.

The military has the added task of rescuing at least 150 hostages, held in unknown locations across Gaza.

Herzi Halevi, chief of staff of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), has vowed to "dismantle" Hamas, and has singled out its political head in Gaza. But is there an ultimate vision for how Gaza will look after 16 years of Hamas's violent rule?

"I don't think Israel can dismantle every Hamas member, because it's an idea of extremist Islam," says military analyst Amir Bar Shalom of Israel's Army Radio. "But you can weaken it as much as you can so it has no operational capabilities."

That might be a more realistic objective. Israel has fought four wars with Hamas, and every attempt to halt its rocket attacks has failed.

Spokesman Lt Col Jonathan Conricus said by the end of this war Hamas should no longer have the military capacity to "threaten or kill Israeli civilians".

Ground invasion fraught with risk

The military operation is at the mercy of several factors that could derail it.

Hamas's armed wing, the Izzedine al-Qassam Brigades, will have prepared for an Israeli offensive. Explosive devices will have been set, and ambushes planned. It can use its notorious and extensive network of tunnels to attack Israeli forces.

In 2014, Israeli infantry battalions suffered heavy losses from anti-tank mines, snipers and ambushes, while hundreds of civilians died in fighting in a northern neighbourhood of Gaza City.

That is one reason Israel has demanded the evacuation of 1.1 million Palestinians from the northern half of the Gaza Strip.

Israelis have been warned the war could take months, and a record 360,000 reservists have reported for duty.

The question is how long Israel can continue its campaign without international pressure to pull back.

Gaza is rapidly becoming a "hell hole", the UN's refugee agency has warned. The death toll is rising fast; water, power and fuel supplies have been cut off, and now half of the population is being told to flee large areas.

"The government and military feel they have the backing of the international community - at least Western leaders. The philosophy is 'let's mobilise, we have plenty of time'," says Yossi Melman, one of Israel's leading security and intelligence journalists.

But sooner or later he believes Israel's allies will step in if they sees images of people starving.

Saving the hostages

Many of the hostages are Israelis, but there also are a large number of foreign citizens and dual nationals among them, so several other governments, including the US, France and the UK have a stake in this operation and their safe release.

President Emmanuel Macron has promised French-Israeli families to bring their loved ones home: "France will never abandon its children."

The extent to which the fate of the hostages will influence military planners is unclear, and there is also domestic pressure on Israel's leaders.

Amir Bar Shalom compares the situation to the 1972 Munich Olympics, when Palestinian gunman seized Israeli athletes and killed 11 people.

An operation was launched to find and kill everyone involved in the attack and he believes the government will want to hunt down all those behind the kidnappings.

Rescuing so many people held in different areas of Gaza may prove beyond the commandos of Israel's elite unit Sayeret Matkal. Hamas has already threatened to shoot hostages as a deterrent to Israeli attack.

In 2011, Israel exchanged more than 1,000 prisoners for the release of a soldier, Gilad Shalit, held by Hamas for five years. But Israel will think twice before another big prisoner release, because one of the men freed in that swap was Yahya Sinwar, who has since become Hamas's political leader in Gaza.

Neighbours watching closely

What could also affect the duration and outcome of a ground offensive is how Israel's neighbours react.

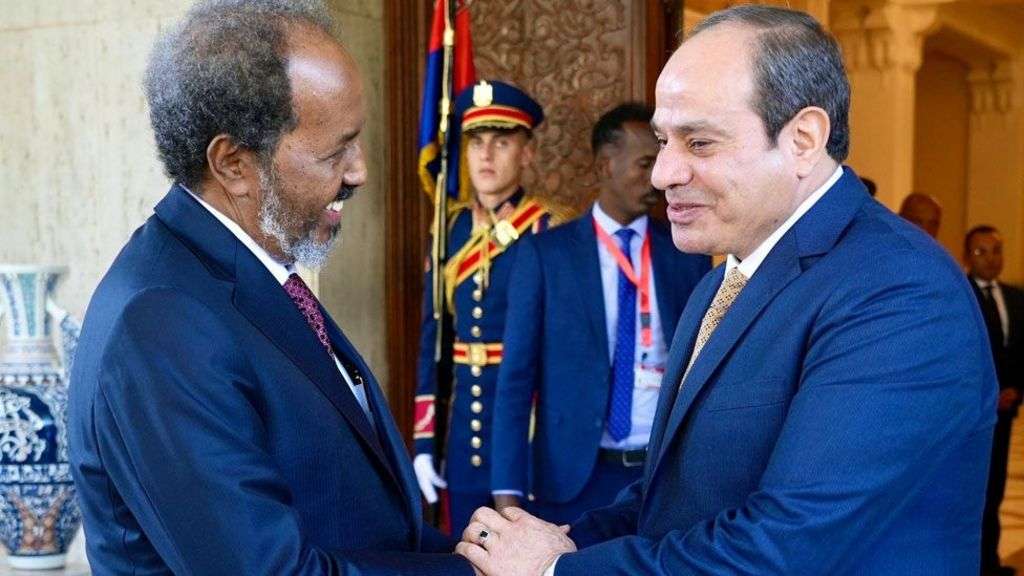

It may face increasing demands from Egypt, which shares a border with Gaza and is already pushing for aid to be allowed through its Rafah border crossing.

"The more that Gazans suffer following the Israeli military campaign, the more pressure Egypt will face, to appear as if it has not turned its back on the Palestinians," says Ofir Winter of Israel's Institute for National Security Studies.

But that will not stretch to Cairo allowing a mass crossing of Gazans into Egypt or acting militarily against Israel on their behalf, he believes.

Israel's northern border with Lebanon is under close scrutiny too.

So far there have been several cross-border attacks involving Islamist militant group Hezbollah, but they have not amounted to a new front against Israel.

Iran, Hezbollah's main sponsor, is already threatening to launch "new fronts" against Israel. They were the focus of US President Joe Biden's warning this week, when he said: "To any country, any organisation, anyone thinking of taking advantage of this situation, I have one word: Don't!"

A US aircraft carrier has been sent to the Eastern Mediterranean to emphasise that message.

What is Israel's endgame for Gaza?

If Hamas were to be significantly weakened, the question is what would go in its place.

Israel pulled its army and thousands of settlers out of the Gaza Strip in 2005 and will have no intention to return as an occupying force.

Ofir Winter believes a shift in power could potentially pave the way for the gradual return of the Palestinian Authority (PA), kicked out from Gaza by Hamas in 2007. The PA, which is not a militant group, currently controls parts of the West Bank.

Egypt too would welcome a more pragmatic neighbour, he argues.

Gaza's devastated infrastructure will ultimately have to be rebuilt in the way it was after earlier wars.

Even before Hamas's atrocities in Israel there were tight restrictions on "dual-use goods" entering Gaza that could have a military as well as a civilian role. Israel will want to impose even heavier restrictions.

There have been calls for a wide buffer zone along the fence with Gaza to provide greater protection for Israeli communities. A former head of its Shin Bet security service, Yoram Cohen, believes a 2km (1.25-mile) "shoot-on-sight" zone will be needed to replace the existing zone.

Whatever the outcome of the war, Israel will want to ensure a similar attack never happens again.