Often called “white gold” and the key component in rechargeable batteries, the metal lithium is so light that it floats on water, but its price has sunk like a stone over the past year.

Due to a combination of falling global sales of electric vehicles, and a world oversupply of lithium ore, the cost of the main lithium compound has fallen by more than three quarters since June 2023.

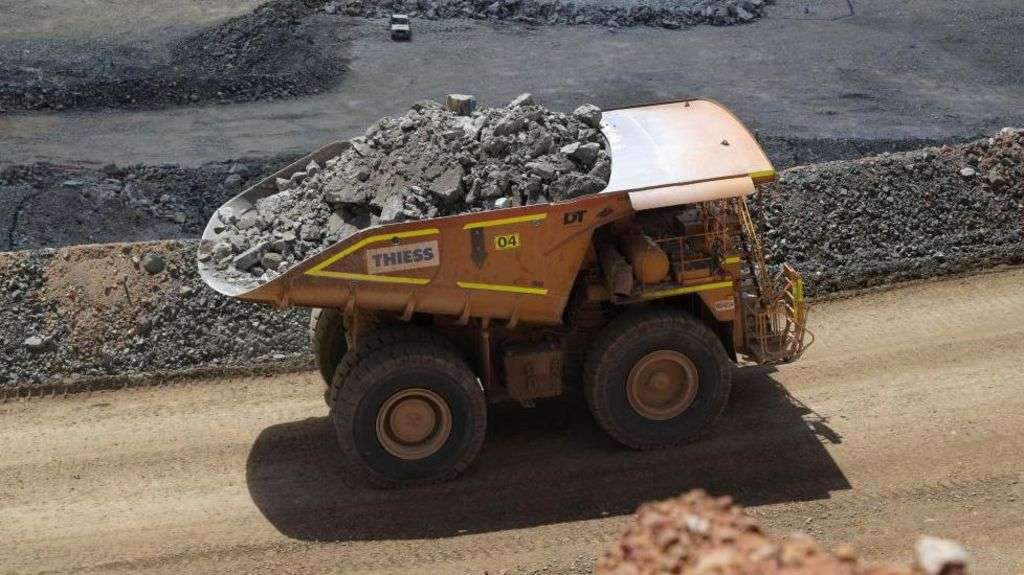

This decline has had a particularly hard impact on Australia, because it is the world’s largest producer of lithium ore, accounting for 52% of the global total last year.

Australia also has the second-largest reserves of the mineral after Chile, with the vast majority in Western Australia, and a smaller amount in the Northern Territory.

The sharp decline in lithium prices has led to mine shutdowns. Adelaide-based Core Lithium announced back in January that due to "weak market conditions" it was suspending mining at its Finniss site near Darwin, with the loss of 150 jobs.

Then in August, US firm Albemarle said it would be scaling back production at its Kemerton lithium processing plant, located some 170km (100 miles) south of Perth. This is expected to lead to more than 300 redundancies.

Arcadium Lithium followed suit this month, announcing that it would be mothballing its Mt Cattlin mine in Western Australia, blaming low prices. The firm’s shares are listed in both the US and Australia.

Yet as some producers are putting work on hold, others are expanding theirs, confident that global demand for lithium - and prices - will bounce back.

Pilbara Minerals is one such firm. The Perth-based miner aims to boost its lithium ore production by an additional 50% over the next year.

“What we've learned historically from lithium pricing is that it can change, and it can change rapidly," managing director Dale Henderson recently told ABC News. “It doesn't faze us that much because we know the long-term outlook is fantastic.”

This confidence is echoed by Kingsley Jones, founder, and chief investment officer at Canberra-based investment firm Jevons Global, which monitors the mining and metals sectors. “Lithium remains very strategic to the energy transition,” he tells the OceanNewsUK.

“Storage batteries for electricity is a big growth area,” he adds, pointing to the increased need for batteries to store the power generated by solar and wind power.

But some analysts have warned that oversupply will keep the market under pressure until at least 2028.

Another company moving ahead with increased lithium ore production in Australia is Perth-based Liontown Resources. In July, it started production at its Kathleen Valley mine, located 420 miles (680km) north-east of Western Australia’s capital.

The facility gets 60% of its energy from its own solar panel farm.

Australia’s Minister for Climate Change and Energy, Chris Bowen, has praised the site’s green approach, and his government has invested $A230m ($156m; £118m) in the facility.

This move towards the use of renewables is also good news in financial terms for producers in Australia, as it reduces their dependence on buying expensive diesel, which is currently the main fuel that they use to generate electricity.

Extracting lithium ore in the country requires three times more energy than in other big producing nations such as Chile and Argentina, says Prof Rick Valenta, the director of the Sustainable Minerals Institute at the University of Queensland.

Extraction in Australia requires additional energy because the lithium ore, also known as spodumene, has to be mined and removed from solid rock. Whereas in Chile and Argentina the ore is produced by evaporating it from brine collected from under the countries' vast salt plains.

“As Australia has hard-rock mining operations, they use more energy and produce more emissions than brine operations,” Prof Valenta adds.

The form of lithium that Australia exports – almost all of which goes to China – is partially processed ore, called spodumene concentrate.

Prices of this have mirrored the sharp fall of refined lithium. One report this month said that the price of spodumene had hit its lowest level since August 2021.

Chinese companies refine the spodumene into solid lithium, and into the two lithium compounds used in batteries - lithium hydroxide and lithium carbonate.

This is where the real money is to be made, because a tonne of lithium carbonate is currently around 72,500 yuan ($10,280; £7,720) compared with just $747 (£630) for the same weight of spodumene concentrate.

Given that price differential, Australian mining firms have unsurprisingly been moving to build their own lithium refineries instead of just exporting almost all spodumene, as is the case currently. In 2022-23, 98% was exported as spodumene concentrate.

The first refined lithium to be commercially produced in Australia happened back in 2022, when Perth-based IGO announced that it was making battery-grade lithium hydroxide at its Kwinana Refinery in Western Australia. It co-owns the facility with Chinese firm Tianqi Lithium.

Meanwhile, another Australian miner, Covalent Lithium, is building its own lithium refinery, also in Western Australia. And Albemarle has its refinery, albeit one currently reducing its output.

Some commentators welcome the development of lithium refining in Australia, saying it will help to reduce China’s dominance of the global market for the metal. China currently accounts for 60% of all lithium refining.

However, Kingsley Jones says that Australia needs to be more open to embracing Chinese investment in the lithium sector. He points out that the Australian government has, in his view, “adopted a strategy, we think unwisely, to preference investment from countries other than China” in the lithium sector in recent years.

This has come as relations between the two countries have cooled since 2020. Last year, Canberra even blocked the sale of an Australian lithium miner to a Chinese firm.

The government said at the time that it was simply following the advice of the country’s Foreign Investment Review Board.

Mr Jones adds: “It’s an excellent example of how to shoot yourself in the foot as a producer. You tell the biggest buyer to go away. So, they do.”

Australia's Department of Industry, Science and Resources did not respond to a request for a comment.

As Australia aims to become more of a lithium refiner, government scientists are continuing to research ways to do this in a more environmentally friendly way. A code, which if cracked, could make the country one of the greenest producers of the metal. Currently the process releases a lot of poisonous chlorine gas.

“There is only one industrial method, and it has several drawbacks,” says Dongmei Liu, a research scientist at Australia’s national science agency, the CSIRO.

“The process is very expensive and not very efficient. Most importantly, it also produces chlorine gas. It has severe environmental issues.”

She and her team are instead working on a new process called “shock quenching”. It involves the extreme cooling of lithium vapour, and Dr Lui says it “avoids the chlorine gas emissions”.

While Australia hopes to make its mineral industries less polluting, it also wants to recycle more.

Lithium Australia is a listed company that sorts and processes batteries that have come to the end of their lives, to extract their lithium and other metals for reuse.

“Global commodities prices place economic pressure on lithium, so creating a circular battery industry will benefit Australia by ensuring we have the sovereign capability to produce and recycle our own batteries,” says Lithium Australia chief executive Simon Linge.

“If Australia is to establish a battery manufacturing industry, we must first ensure that no end-of-life lithium battery is being sent to landfill or exported to be recycled in some other country.”