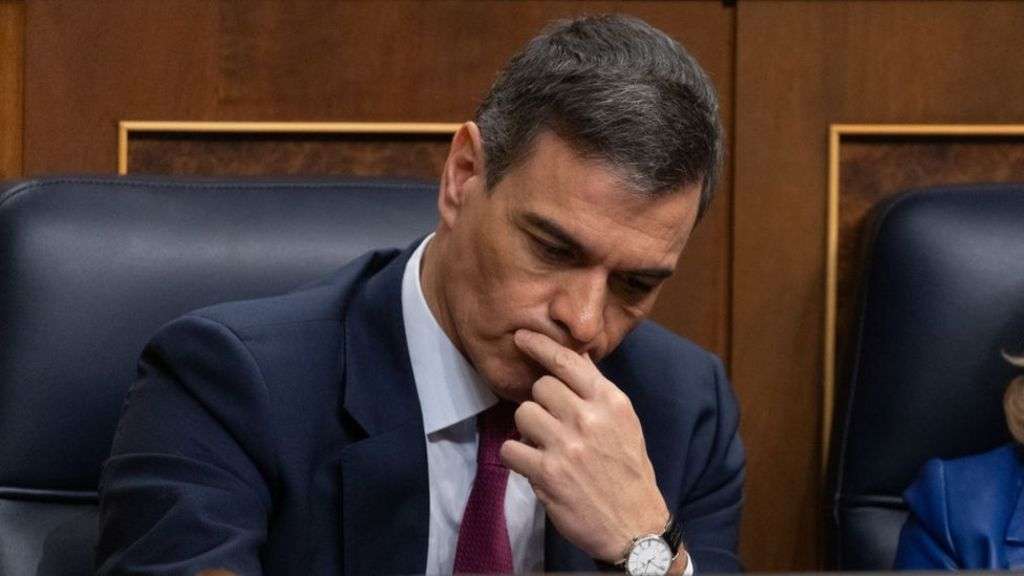

On Monday morning, Spanish prime minister Pedro Sánchez announced he would remain in office following several days of intense speculation over his future. The decision may have averted a political crisis, but it risks deepening the country's schism between left and right. The Socialist leader made the announcement from outside his La Moncloa official residence, promising to "work tirelessly, with firmness and calm, for the pending regeneration of our democracy and for the advance and consolidation of rights and freedoms." He thus avoided becoming the first prime minister to resign during a legislature since Adolfo Suárez, in 1981. This confirmation that he would continue came just five days after Mr Sánchez had surprised Spaniards, and even many of his closest allies, by announcing he was cancelling official engagements in order to consider his future.

The abrupt move was triggered by the revelation that a court in Madrid had opened an inquiry into his wife, Begoña Gómez, due to allegations of influence peddling brought against her by a campaigning group, Manos Limpias (Clean Hands) with links to the far-right.

The preliminary investigation is examining whether Ms Gómez influenced the awarding of government money to private companies.

Specifically, it is examining the relationship between a foundation she ran called IE Africa Center and tourism group Globalia, whose airline Air Europa received a bailout worth €475m (£407m) during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The evidence presented in the lawsuit consisted entirely of news clippings, one of which has already been shown to be false. Mr Sánchez and Ms Gómez have said the allegations, which had been published by right-wing media outlets for several weeks, are bogus. The Madrid public prosecutor has called for the case to be shelved due to lack of evidence.

However, it was enough to push Mr Sánchez to decry, in a letter he posted on social media last week, what he described as "a coalition of interests on the right and far right" which refused to accept his government as legitimate.

"They were conscious that political attacks would not be enough and now they have crossed the line of disrespecting the family life of a prime minister and [are attacking] his personal life," he wrote.

Throughout his career, the 52-year-old Mr Sánchez has taken dramatic, often risky, decisions. These have included presenting a no-confidence motion against his predecessor as prime minister, Mariano Rajoy, which allowed him to take office; calling a first-ever summer general election hours after suffering severe losses in last year's local elections; and presenting a controversial amnesty law for Catalan nationalists.

Yet his willingness to consider resigning, while typically drastic, does not appear to have been driven by the political calculation for which Mr Sánchez has become known.

In recent years, Spain has succumbed to what centre-left newspaper El País calls "the barbarisation of political life".

Politicians on the left have felt particularly targeted by this. The former leader of the far-left Podemos party, Pablo Iglesias, was one prime example, having to return from a family holiday in the north of Spain because of the abuse he received there, as well as having a group of far-right activists gathering outside his home for several weeks.

Since Mr Iglesias's withdrawal from politics, Mr Sánchez has taken on the status of lightning rod for the right.

Last New Year's Eve, protesters strung up an effigy of the prime minister outside his Socialist Party's headquarters and beat it with sticks.

False conspiracy theories about his family have been circulating in the right-wing media, including the claim that Ms Gómez was transgender and had links to drug trafficking.

With the influence-peddling case presented by Clean Hands, the prime minister seems to believe that the campaign against him has moved into the judicial sphere and that this reflects a weakness not just in the country's politics - but also in its justice system.

"If we allow deliberate falsehoods to set the political debate, if we force victims of these lies to have to show their innocence against the most basic principle of our rule of law… we will have done irreparable damage to our democracy," Mr Sánchez said as he vowed to remain in office.

In Spain, lawsuits can be brought by parties who are not victims in a case. This has meant that Clean Hands, for example, has been able to present a litany of judicial proceedings against politicians in recent years - although most of them have not flourished.

Many other politicians have complained, and more directly than Mr Sánchez, of the use of the judiciary as a political weapon against them, a practice also known as "lawfare". The far-left Podemos party and Catalan nationalists, for example, have claimed to be targets of investigations based on fabricated evidence.

"Pedro Sánchez stays. And lawfare too?" wrote Podemos's former equality minister Irene Montero.

However, many will question Mr Sánchez's assertion that "things are going to be different" in the wake of his five-day hiatus. There is no reason to think that the toxic atmosphere which has taken hold of Spanish politics will lift any time soon.

The right-wing opposition sees Mr Sánchez's handling of the case against his wife as both provocative and liable to undermine the judiciary.

This is likely to be a frequent course of attack in the weeks and months to come against a prime minister whose parliamentary reliance on Catalan and Basque separatists has long drawn accusations of constitutional recklessness.

"Spain hasn't travelled this long road just to end up emulating regimes which do not believe in freedom," Alberto Núñez Feijóo, leader of the conservative People's Party (PP), said, in response to the prime minister's statement.

Mr Sánchez has steered the country away from some of the possible political avenues which had loomed in recent days - such as a caretaker government, a parliamentary confidence vote, or even new elections.

But his decision to remain is unlikely to calm the fierce tone of Spanish politics.