After more than a year of anticipation leading up to Donald Trump's first criminal trial, it got underway Monday, offering a taste - and some clues - about the tone and legal strategies the next several weeks may bring. We got a glimpse of Mr Trump's courtroom demeanour in a criminal trial. The prosecution's case finally crystallised around a grand theory of election interference as key witnesses laid the groundwork. And flashes of tension may have opened a rift between Judge Juan Merchan and Mr Trump's lead attorney. Something that became immediately clear in court is that this trial will be an endurance test, perhaps for Mr Trump most of all.A marathon for Trump

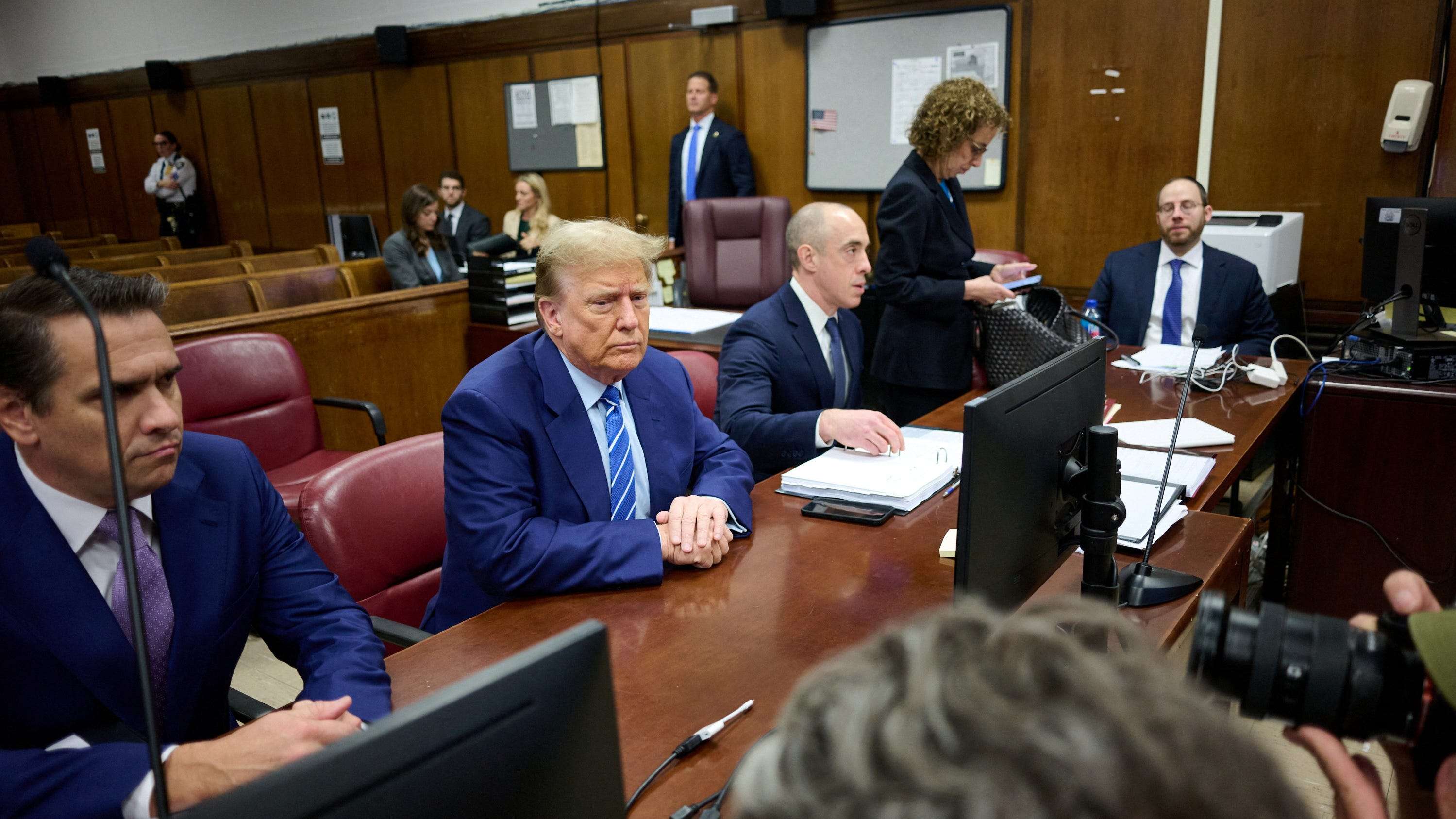

For the last year, the 77-year-old has actively campaigned for president during cases where he wasn't required to be present. Now, he must appear in court each day of this trial. That means Mr Trump will sit for hours at the defence table.

The former president appears thinner - he told Fox News in January that he lost weight - and his stride varies. At times, he moves slower, and at others, he confidently strides into courtroom - the same one where he sat a year ago for his arraignment pleading not guilty to all 34 felony charges.

Also unlike previous civil trials, when Mr Trump made audible comments from the defence table and argued with judges, he has been far more compliant.

"One interesting dynamic is how differently Trump the criminal defendant is behaving, in comparison to Trump the civil litigant," said Anna Cominsky, a professor at New York Law School.

"We have seen a much more subdued and controlled Trump while he is in front of the jury."

During the proceedings, he confers with his lead attorney, Todd Blanche, in urgent whispers.

"It's an incredibly difficult process to sit through, especially trials like this that may last many, many weeks," said Dmitriy Shakhnevich, a criminal defence attorney in Manhattan.

Mr Trump repeatedly has aired his frustrations publicly.

"I'm not allowed to say anything," he told reporters stationed just outside the courtroom doors on Tuesday, after a hearing about his gag order.

'I'd love to say everything that's on my mind," he added.

What we learned about the Manhattan District Attorney's case

At the heart of the case is the alleged cover-up of a hush money payment Mr Trump's lawyer made to an adult film star before the 2016 election, but prosecutors have hinted for months at something greater.

This week, they solidified their case.

"This was a planned, coordinated, long-running conspiracy to influence the 2016 election," prosecutor Matthew Colangelo said in his opening remarks Monday.

"It was election fraud, pure and simple," Mr Colangelo later added.

They aim to convince the jury not only that Mr Trump committed the misdemeanour of falsifying business records to hide a hush money payment carried out by his lawyer, but that he did so in order to conceal or aid a second crime, making the offense more serious.

Prosecutors have suggested Mr Trump sought to violate state or federal election laws, and state tax laws, and Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg hinted his team would pursue an election interference argument.

Their first witness, former National Enquirer publisher David Pecker, helped bolster this case.

He testified about an "agreement" involving himself, Mr Trump and lawyer Michael Cohen to use the tabloid to boost Mr Trump's 2016 campaign. Mr Pecker testified he agreed to provide positive coverage of Trump and head off potentially damaging stories.

Payouts Mr Pecker facilitated to block one such story also may have run afoul of federal election laws, prosecutors suggested through the questioning.

"They have just started to scratch the surface of the conspiracy to affect the election, so it's yet to be seen how convincing their evidence is on this," Ms Cominsky said.

In a cross examination, Mr Trump's defence attorney Emil Bove sought to paint such an arrangement as business as usual for Mr Pecker.

But some have told the OceanNewsUK it is not clear state election statutes apply neatly to Mr Trump's case, nor is it settled whether a state prosecutor can invoke a federal crime.

"I think the election interference theory that the prosecution is pushing raises the likelihood of a jury conviction," John Coffee of Columbia Law School said of the prosecution's approach.

"But [it] risks raising appellate and constitutional issues on appeal."

Trump's lead attorney's rocky start with the court

In one of the most dramatic moment of the trial so far, Judge Merchan clashed with the defence during a hearing on whether or not Mr Trump had violated a gag order.

Mr Blanche repeatedly ran afoul of the judge Tuesday in an episode that Mr Coffee said "did not augur well" for him or for Mr Trump.

At the climax of a testy exchange, Mr Blanche claimed his client was being "very careful" not to violate the gag order and was merely responding to political campaign attacks.

But when he did not cite specific examples, Justice Merchan fumed, "You're losing all credibility with the court."

Next Thursday, the two will face off again in a second hearing related to the gag order.

"Judge Merchan's reaction to him was clearly negative and hostile," said Mr Coffee. "That is well out of line from typical judicial practice and suggests that the court does not have confidence or respect for him."

While Mr Blanche is working with the facts he has, Ms Cominsky said, it is still tricky.

"There is a fine line between zealous advocacy and frivolous arguments. The court appears to be losing patience with some of the arguments,'' she said.