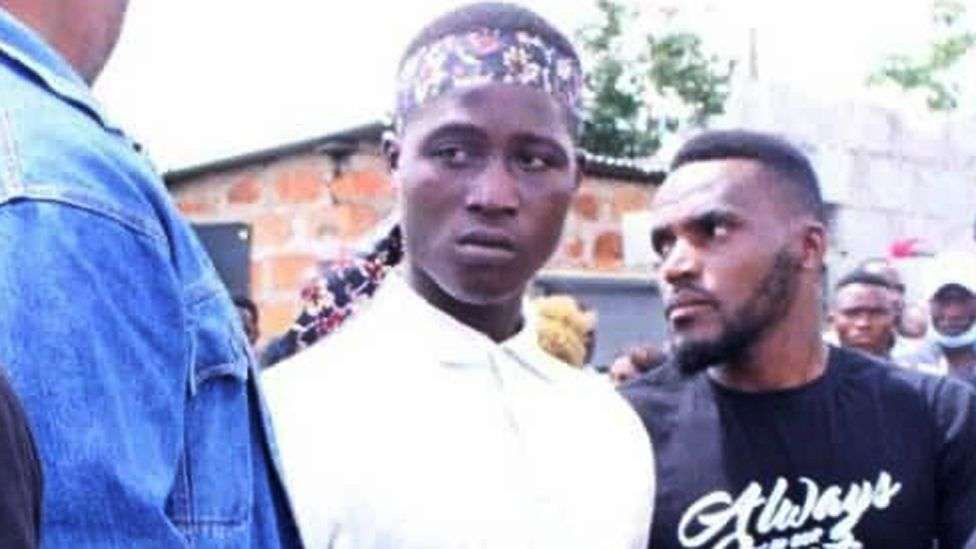

I met Andrew Kazadi just after his 26-year-old nephew died of cholera at a treatment centre in Zambia's capital, Lusaka. He looked deeply traumatised.

"We have been told to look for a coffin but if we delay, they'll bury him just like that," Mr Kazadi said, in comments reminiscent of some of the restrictions governments imposed during the coronavirus pandemic.

Now, cholera, a bacterial infection caused by contaminated water or food, is wreaking havoc in Zambia, with more than 15,000 cases and close to 600 deaths recorded, mostly in the hotspot of Lusaka, since the beginning of the rainy season in October.

And as clouds gathered over the skies before another downpour, Mr Kazadi said: "We have to hurry to get a coffin."

I met him outside the 60,000-seater Heroes Stadium, which has been turned into a treatment centre with about 800 medics attending to patients from across the country.

The sound of the wailing sirens of ambulances is constant. Patients are brought in or taken for burial after succumbing to the disease.

For Mr Kazadi, to see the lifeless corpse of Charles, his sister's son, came as a shock.

Charles suffered a bout of diarrhoea and was vomiting. He was taken to a clinic, where the family was told he had cholera.

He was then transferred to the stadium - normally a venue for football matches - where he died eight days later.

"Our expectation was that he would be fine with the passage of time. We are really grieving as a family," Mr Kazadi said, pointing out that his nephew has left behind a three-year-old.

But in a sign of the family's deep faith, he added: "When someone is sick, we commit everything into God's hands - that person can either die or survive. With all the challenges we have gone through, we just have to thank God."

In line with government regulations to curb the spread of the disease, Charles' corpse was wrapped in a body bag, before being placed in the coffin by men wearing protective gear.

The family was not allowed to touch the body to protect them from the risk of infection. Only five relatives were allowed to attend Charles' burial.

The government's guidelines are similar to those of the World Health Organization (WHO), which advises that families should handle the body as little as possible, and burials should preferably take place within 24 hours.

"Gastrointestinal infections [like cholera] can easily be transmitted from faeces leaked from dead bodies," the WHO says.

Sadly, some families in Lusaka are going through a trauma different from that of the Kazadis.

They do not know the fate of their loved ones, as over-stretched health workers have been been unable to tell them about their condition - or whether they are even alive.

They include Eunice Chongo, who told me that her 34-year-old son, Boniface, was brought by ambulance to the stadium about a week ago, but she has not heard anything about him since then.

"All I want is for the government to tell me the truth about the whereabouts of my son," Ms Chongo said, looking distressed.

The government has set up a call centre, urging people like Ms Chongo to report missing family so that they can help trace them.

Zambia has experienced cholera outbreaks at least 30 times since 1977, with the charity WaterAid saying the latest one is the worst since 2017.

This is despite the fact that the government pledged in 2019 to eliminate the disease by 2025.

WaterAid's Zambia director Yankho Mataya said the government would not meet its goal "without greater increased investment and improved co-ordination to address the root cause - lack of access to clean water and decent sanitation".

Research published in 2019 showed that a staggeringly high number of Zambians - 40% - lived without adequate clean water, while as many as 85% lacked access to proper solid waste management.

The coordinator of Zambia's Disaster Management and Mitigation Unit, Gabriel Pollen, said data was still being collected to assess what progress had been made since 2019 to improve water and sanitation facilities.

"The numbers are quite alarming, and we do see here reluctance on the part of communities in terms of hygiene," he said.

The cholera hot-spots in Lusaka are poor neighbourhoods, known locally as compounds, where people live in slum-like conditions.

Often pit latrines are built too close to shallow wells, from where drinking water is drawn.

When it rains, the water level rises, along with the risk of human waste contaminating the water - and poor drainage causes this water to flood homes.

To fight the disease, a raft of measures have been introduced by the government, including a ban on the digging of shallow wells, and the selling of food in unhygienic conditions.

In a speech earlier this month, President Hakainde Hichilema promised also to upgrade poorly planned informal settlements, and to prevent new ones from emerging.

Some young people were "hanging around and doing nothing" in cities and towns instead of moving to rural areas to farm, the president said.

"There is so much land in the villages. There is clean water. We can build nice homes in the villages, which are not polluted," he added.

While the government may see the decongestion of cities as a long-term solution, its priority right now is to prevent the further loss of life through a vaccination campaign.

It received about 1.6 million doses earlier this month, and has so far administered the large majority of them, mostly in Lusaka.

"The response has been overwhelming. We are just worried whether we will be able to cover the hotspots with the doses we have," Health Minister Sylvia Masebo said, at a public briefing.

But she said there was some hesitancy, including among some religious groups.

Ms Masebo did not go into details, but some are known to believe that vaccines make them spiritually impure.

To them, her message was: "Please let us not be swayed by such beliefs. We all know that true religion aims at safe-guarding the health of believers."

Ms Masebo also identified vaccine hesitancy in another group - young men.

Again, she did not go into details, but appeared to be referring to the fact that some of them believe they do not need to be vaccinated as they have a strong immune system.

Other men have been drinking more beer, as they believe it kills the bacteria which causes cholera.

In what appeared to be a message directed at them, Ms Masebo said people should spend their money on chlorine - which kills bacteria in water - rather than beer.

But Ms Masebo will have to repeat the message much more, before changing the beliefs of the young men who are increasingly frequenting the beer halls of Lusaka.