In November 2019, the OceanNewsUK reported on Shams Erfan, a 21-year-old Afghan who fled the Taliban, alone, as a teenager. We met him in Indonesia, where he was stuck in a refugee camp - one of millions worldwide with only a tiny chance of starting a new life. Four years later, he writes his own story.

On the afternoon of 8 November 2021, I sat on the cement stairs inside the International Ferry Terminal in the city of Batam, Indonesia. It was a three-minute walk from the refugee shelter where I lived; an escape from the camp's small, dark and windowless rooms.

Two cargo ships were parked on the other side of the terminal promenade. I watched the men unloading sacks of rice and flour from the ship. The warm salty water, breaking against the cement wall of the promenade, splashed on my face.

With nowhere to go, I found another bench, at the east end of the terminal, under the shade of a coconut tree. I could see the ferries full of tourists leaving Batam for Singapore, just across the water. I became lost in imagination, dreaming of freedom.

Soon, I had to return to the shelter's small, cramped rooms, to meet the 6pm curfew. To distract myself, I opened my phone. There was an email.

It was from the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

I had been in Indonesia since fleeing Afghanistan in December 2014, aged 15. Back then, on a trip to Kabul to pick up supplies for the English-language school where I worked, Taliban gunmen hijacked my bus, looking to kill the "English teacher".

As the gunmen slapped my face, a stranger saved my life. But even then, I knew: I had to leave Afghanistan. I fled to Delhi, then Kuala Lumpur, before taking a wooden boat across the Strait of Malacca. After bouncing around various sites in Indonesia, in 2016 I found myself in Pontianak, a prison camp for asylum seekers.

Resettlement rates from Indonesia to third countries, via the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), were low. The chances of receiving an individual resettlement offer were almost non-existent. Certainty seemed elusive.

In prison, I wrote a blog about the living conditions of refugees, like me, who were trapped. My audience was small but supportive. One evening in 2018, as the last rays of the sun disappeared behind the razor wire-topped walls, and a dark, unwelcome cloud obscured the blue skies, I got a message from Canada.

It was from Renee Oettershagen, a lady from Burlington, Ontario. Renee had read my work and we had become friends. I connected her with friends in Australia - Denise, Lindy, Diana, and Jane - who were also eager to help me escape Indonesia. They had read my work and wanted me to live somewhere as a normal citizen, with full rights, rather than the in-limbo, locked-up life of an asylum seeker.

Our team discovered that I was eligible to apply for permanent residency in Canada through the Group of Five programme. Under this programme, groups of Canadians living in one community could form a group to sponsor a refugee, so long as they were already recognised by the UNHCR, which I was.

To begin the paperwork, we needed 16,500 Canadian dollars (£9,825) held in a bank account, allocated for my first year's living expenses in Canada. It was a daunting sum, and raising it seemed impossible.

That evening, as I walked in circles on the prison's dirt ground, Renee messaged me with incredible news. She and her husband, Bill, had agreed to welcome me into one of their empty bedrooms in their house.

As I burst into laughter, amazed that these Australians and Canadians had opened their hearts and homes, the security guard yelled at me to return to my cell.

Despite the guard's anger, half my problem was resolved - we now only needed 8,000 CAD. The other half of the funds was raised between my Australian friends, and we needed three more Canadians to join the team the Group of Five.

Another woman, Wendy Noury Long, became aware of my story. She joined the team with her husband and son, and we submitted my application to the government of Canada in January 2020.

Almost two years later, I sat at the Batam ferry terminal and read the email from the IOM.

"We have scheduled your flight to move to Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia, to complete your medical examination and biometric process at the Canadian embassy, in order to leave Indonesia for Canada."

In order to leave Indonesia for Canada.

I read the email five times. Maybe he sent it by mistake? I washed my face in the terminal's bathroom with cold water, then took a long, deep breath.

I turned on my internet and read the email again. It was for me. I saw my name. It was real.

I'm leaving. My application for permanent residency in Canada was accepted.

The news flowed through my veins like a morning breeze, propelling my body to run towards the shelter to meet the curfew. Arriving five minutes late would mean being sent to solitary confinement.

A local man, who had a few packs of instant coffee and noodles on his cart, was sitting on a portable red plastic chair outside the terminal gate. He had taken off his shirt and was using it to dry the sweat dripping from his forehead.

As I walked past, he called me "Orang Migran" - a refugee man. The words echoed in my ears, like congratulations for surviving eight years of life in detention. I felt lighter. The trees lined up on both side of the roads, gently rustling, celebrating the news with me.

The next day, I went to Jakarta. I completed my medical examination at a hospital, and two months later, completed my biometrics at the Canadian embassy.

It still felt surreal. While in the embassy, I could almost smell Canada.

My flight to Canada was scheduled for 3 March 2022. As the IOM dropped me off at the airport in Jakarta, I couldn't believe I was there, waiting for my flight to take off.

In my hand, I held the travel document and ticket issued by the Canadian government. I kept looking at them, doubting their authenticity. At the same time, my eyes continued to scan every corner of the waiting room, looking for immigration officers who might order me back to the refugee shelter.

Finally, the call for the flight came. Unlike the camps, there was no immigration officer to accompany me. When I needed to use the restroom, I went alone. When I wanted a cup of tea, the number wasn't monitored.

We finally landed at Istanbul Airport where I waited, tired and red-eyed, for the connecting flight to Canada. But I couldn't sleep.

The night before, the IOM said they would pick me up at midday. I couldn't settle, fearing the immigration guards would find an excuse to cancel my flight if I were late.

Now - despite being awake for 30 hours - I still couldn't risk napping on the bench and missing my flight to Canada. So I stayed awake, my dry eyes blinking, my excitement rising.

Finally, I boarded the plane. The screen on the back of the seat showed our location. As the plane flew over Europe and got farther away from Indonesia, my dream of seeing something - anything - outside Indonesia since 2014 was coming true.

As the plane began its descent, almost everyone seemed calm, their expressions revealing no sign of excitement or happiness. I was different.

The snowy landscape of Toronto came into view. My heart beat faster. Finally, it was my turn to disembark. The passengers walking alongside me to the terminal blew on their hands to keep them warm. The mother who sat next to me on the plane took off her jacket and wrapped it around her child's body.

My coat, which was considered warm in Indonesia, did nothing to keep out the cold. But right then, I didn't notice it. The excitement of arriving in Canada overcame any of that.

Walking toward the airport terminal, I realised, again, there were no guards accompanying me. In the past eight years in Indonesia, every time I was transferred from one detention centre to another, there were always at least 10 guards monitoring my every move. Now I was free.

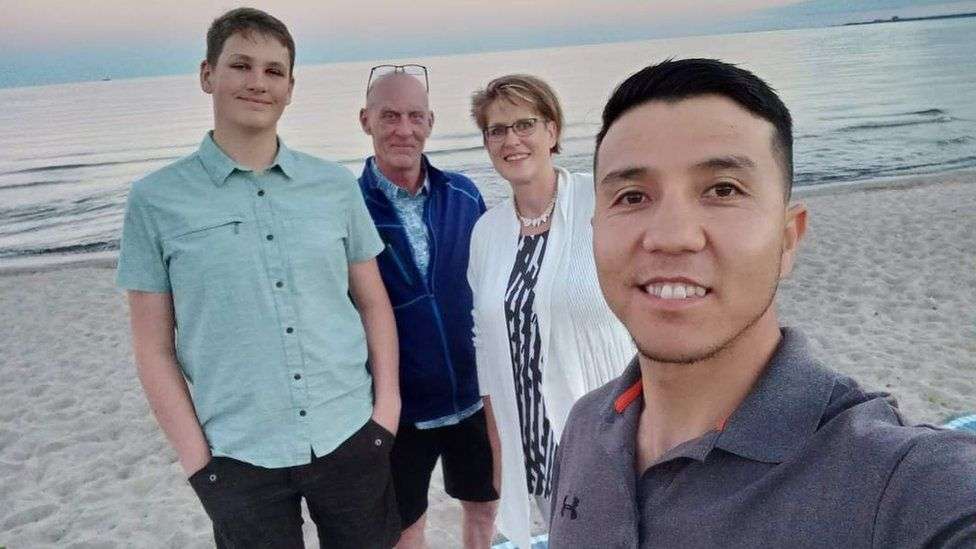

I walked alone through the airport gate to meet my sponsors, who were holding a sign that read: "Welcome Shams".

Outside it was still cold, but the welcome made my body glow. My sponsors had only met me online. To them, I was a stranger.

During my eight-year imprisonment in Indonesian prison camps, I blogged anonymously about the refugees' living conditions, hoping to bring our plight to the world's attention. To be safe, I had to use a pen name.

But that night, everyone called me by my own name. I was no longer invisible. I was no longer a label; an "illegal"; a number. I'd escaped the Taliban's attempt to kill me, only to endure eight years imprisonment in Indonesia. At last, thanks to my sponsors and their friends, I was free.

Shams Erfan, 25, is a permanent resident in Canada and will take the Canadian citizenship test in 18 months' time. He is a writer-in-residence at the George Brown College in Toronto and studies at the University of Toronto, with plans to become a human rights and immigration lawyer.